Uncertainty and sensitivity analysis of GiveWell's top charity rankings

Arguably, we don’t care about the exact cost-effectiveness estimates of each of GiveWell’s top charities. Instead, we care about their relative values. By using distance metrics across these multidimensional outputs, we can perform uncertainty and sensitivity analysis to answer questions about:

- how uncertain we are about the overall relative values of the charities

- which input parameters this overall relative valuation is most sensitive to

Contents

In the last two posts, we performed uncertainty and sensitivity analyses on GiveWell’s charity cost-effectiveness estimates. Our outputs were, respectively:

- probability distributions describing our uncertainty about the value per dollar obtained for each charity and

- estimates of how sensitive each charity’s cost-effectiveness is to each of its input parameters

One problem with this is that we are not supposed to take the cost-effectiveness estimates literally. Arguably, the real purpose of GiveWell’s analysis is not to produce exact numbers but to assess the relative quality of each charity evaluated.

Another issue is that by treating each cost-effectiveness estimate as independent we underweight parameters which are shared across many models. For example, the moral weight that ought to be assigned to increasing consumption shows up in many models. If we consider all the charity-specific models together, this input seems to become more important.

Metrics on rankings

We can solve both of these problems by abstracting away from particular values in the cost-effectiveness analysis and looking at the overall rankings returned. That is we want to transform:

| Charity | Value per $10,000 donated |

|---|---|

| GiveDirectly | 38 |

| The END Fund | 222 |

| Deworm the World | 738 |

| Schistosomiasis Control Initiative | 378 |

| Sightsavers | 394 |

| Malaria Consortium | 326 |

| Against Malaria Foundation | 247 |

| Helen Keller International | 223 |

into:

- Deworm the World

- Sightsavers

- Schistosomiasis Control Initiative

- Malaria Consortium

- Against Malaria Foundation

- Helen Keller International

- The END Fund

- GiveDirectly

But how do we usefully express probabilities over rankings1 (rather than probabilities over simple cost-effectivness numbers)? The approach we’ll follow below is to characterize a ranking produced by a run of the model by computing its distance from the reference ranking listed above (i.e. GiveWell’s current best estimate). Our output probability distribution will then express how far we expect to be from the reference ranking—how much we might learn about the ranking with more information on the inputs. For example, if the distribution is narrow and near 0, that means our uncertain input parameters mostly produce results similar to the reference ranking. If the distribution is wide and far from 0, that means our uncertain input parameters produce results that are highly uncertain and not necessarily similar to the reference ranking.

Spearman’s footrule

What is this mysterious distance metric between rankings that enables the above approach? One such metric is called Spearman’s footrule distance. It’s defined as:

\[d_{fr}(u, v) = \sum_{c \in A} |\text{pos}(u,c) - \text{pos}(v, c)|\]

where:

- \(u\) and \(v\) are rankings,

- \(c\) varies over all the elements \(A\) of the rankings and

- \(\text{pos}(r, x)\) returns the integer position of item \(x\) in ranking \(r\).

In other words, the footrule distance between two rankings is the sum over all items of the (absolute) difference in positions for each item. (We also add a normalization factor so that the distance varies ranges from 0 to 1 but omit that trivia here.)

So the distance between A, B, C and A, B, C is 0; the (unnormalized) distance between A, B, C and C, B, A is 4; and the (unnormalized) distance between A, B, C and B, A, C is 2.

Kendall’s tau

Another common distance metric between rankings is Kendall’s tau. It’s defined as:

\[d_{tau}(u, v) = \sum_{\{i,j\} \in P} \bar{K}_{i,j}(u, v)\]

where:

- \(u\) and \(v\) are again rankings,

- \(i\) and \(j\) are items in the set of unordered pairs \(P\) of distinct elements in \(u\) and \(v\)

- \(\bar{K}_{i,j}(u, v) = 0\) if \(i\) and \(j\) are in the same order (concordant) in \(u\) and \(v\) and \(\bar{K}_{i,j}(u, v) = 1\) otherwise (discordant)

In other words, the Kendall tau distance looks at all possible pairs across items in the rankings and counts up the ones where the two rankings disagree on the ordering of these items. (There’s also a normalization factor that we’ve again omitted so that the distance ranges from 0 to 1.)

So the distance between A, B, C and A, B, C is 0; the (unnormalized) distance between A, B, C and C, B, A is 3; and the (unnormalized) distance between A, B, C and B, A, C is 1.

Angular distance

One drawback of the above metrics is that they throw away information in going from the table with cost-effectiveness estimates to a simple ranking. What would be ideal is to keep that information and find some other distance metric that still emphasizes the relationship between the various numbers rather than their precise values.

Angular distance is a metric which satisfies these criteria. We can regard the table of charities and cost-effectiveness values as an 8-dimensional vector. When our output produces another vector of cost-effectiveness estimates (one for each charity), we can compare this to our reference vector by finding the angle between the two2.

Results

Uncertainties

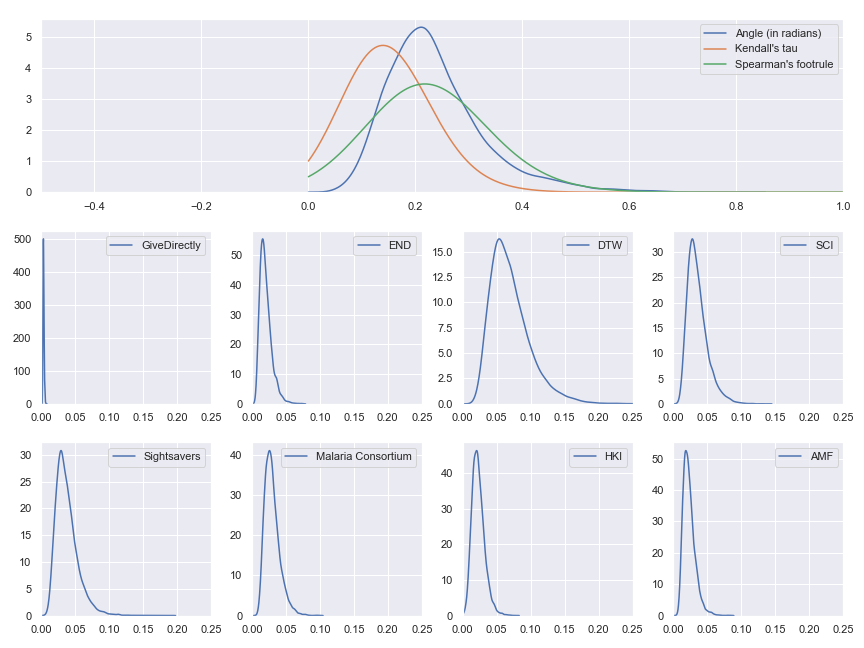

To recap, what we’re about to see next is the result of running our model many times with different sampled input values. In each run, we compute the cost-effectiveness estimates for each charity and compare those estimates to the reference ranking (GiveWell’s best estimate) using each of the tau, footrule and angular distance metrics. Again, the plots below are from running the analysis while pretending that we’re equally uncertain about each input parameter. To avoid this limitation, go to the Jupyter notebook and adjust the input distributions.

We see that our input uncertainty does matter even for these highest level results—there are some input values which cause the ordering of best charities to change. If the gaps between the cost-effectiveness estimates had been very large or our input uncertainty had been very small, we would have expected essentially all of the probability mass to be concentrated at 0 because no change in inputs would have been enough to meaningfully change the relative cost-effectiveness of the charities.

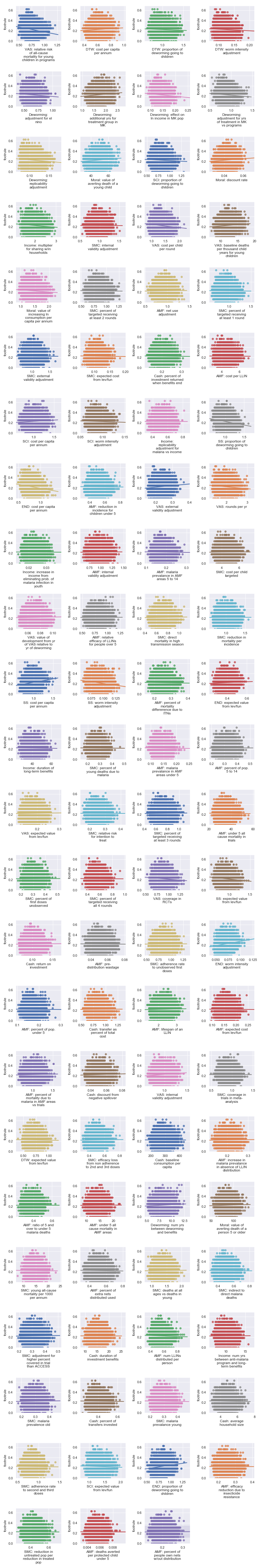

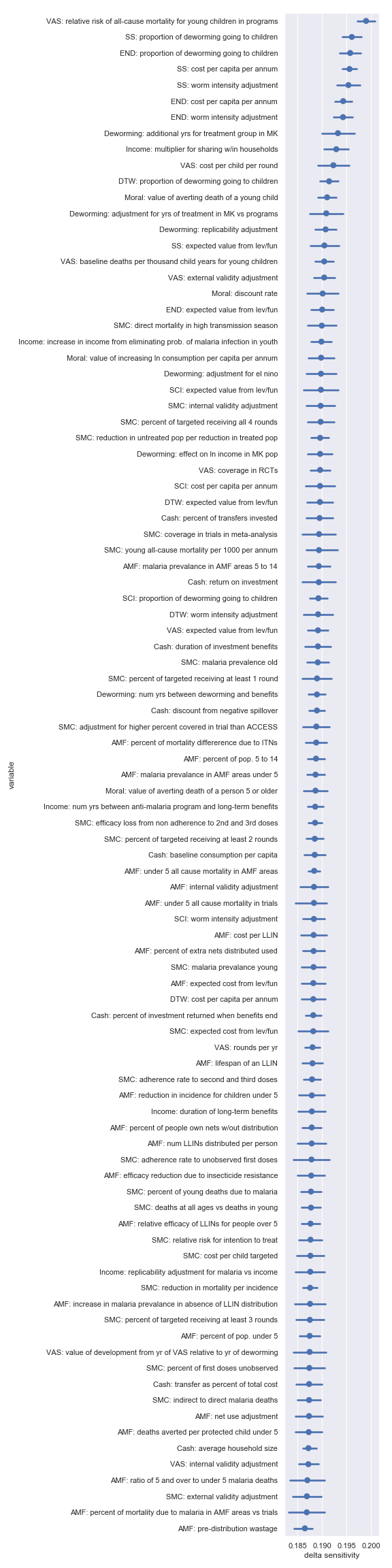

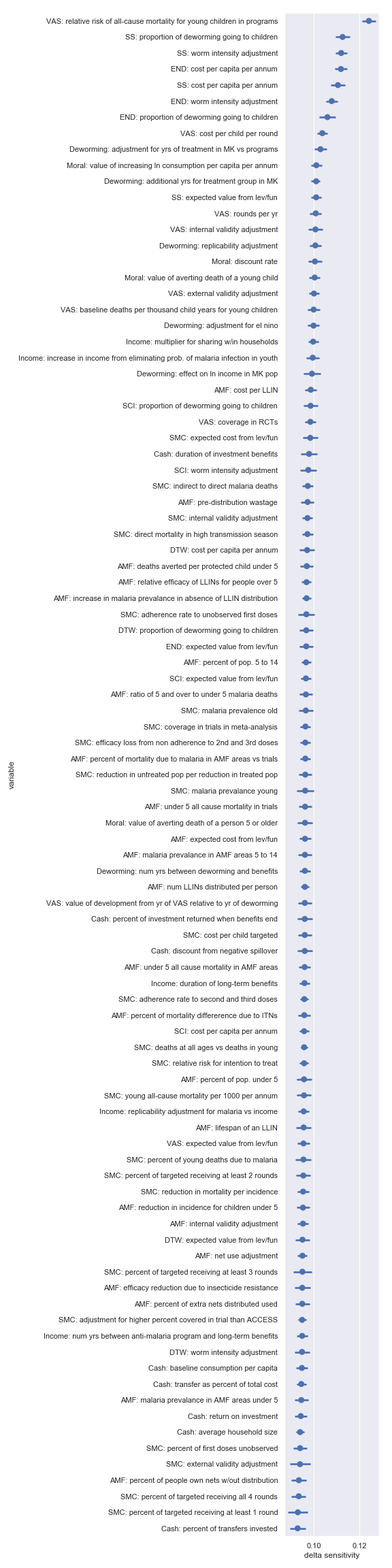

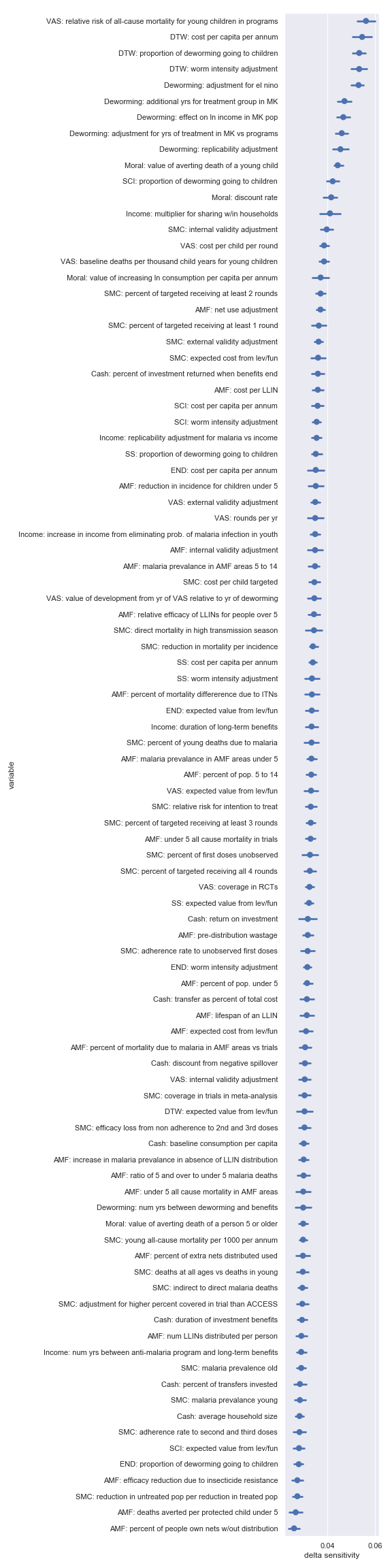

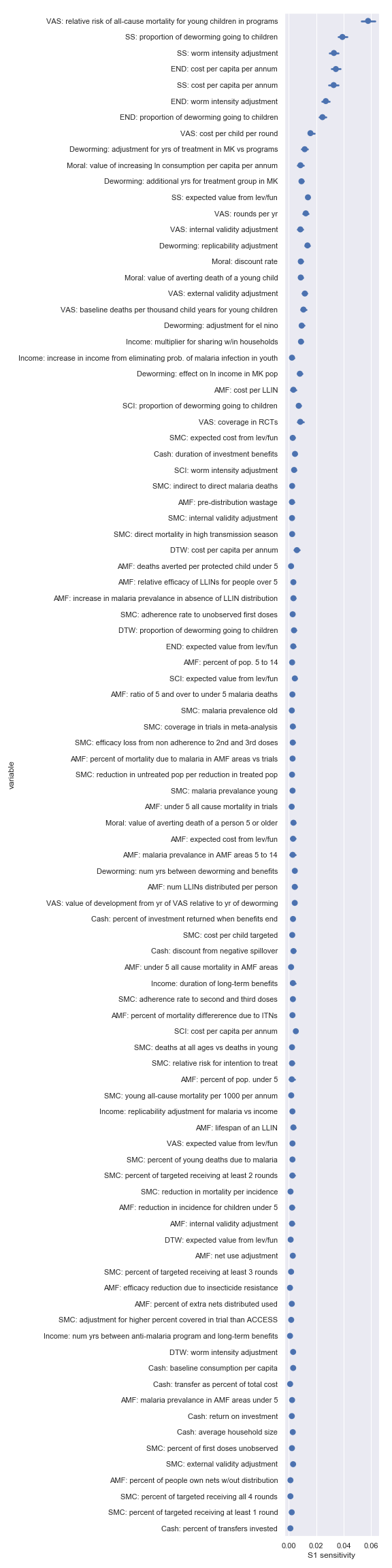

Visual sensitivity analysis

We can now repeat our visual sensitivity analysis but using our distance metrics from the reference as our outcome of interest instead of individual cost-effectiveness estimates. What these plots show is how sensitive the relative cost-effectiveness of the different charities is to each of the input parameters used in any of the cost-effectiveness models (so, yes, there are a lot of parameters/plots). We have three big plots, one for each distance metric—footrule, tau and angle. In each plot, there’s a subplot corresponding to each input factor used anywhere in the GiveWell’s cost-effectiveness analysis.

(The banding in the tau and footrule plots is just an artifact of those distance metrics returning integers (before normalization) rather than reals.)

These results might be a bit surprising at first. Why are there so many charity-specific factors with apparently high sensitivity indicators? Shouldn’t input parameters which affect all models have the biggest influence on the overall result? Also, why do so few of the factors that showed up as most influential in the charity-specific sensitivity analyses from last time make it to the top?

However, after reflecting for a bit, this makes sense. Because we’re interested in the relative performance of the charities, any factor which affects them all equally is of little importance here. Instead, we want factors that have a strong influence on only a few charities. When we go back to the earlier charity-by-charity sensitivity analysis, we see that many of the input parameters we identified as most influential where shared across charities (especially across the deworming charities). Non-shared factors that made it to the top of the charity-by-charity lists—like the relative risk of all-cause mortality for young children in VAS programs—show up somewhat high here too.

But it’s hard to eyeball the sensitivity when there are so many factors and most are of small effect. So let’s quickly move on to the delta analysis.

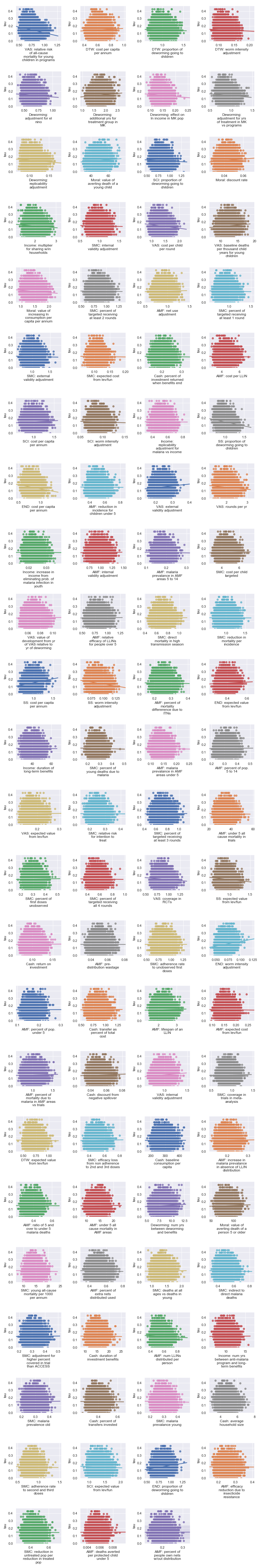

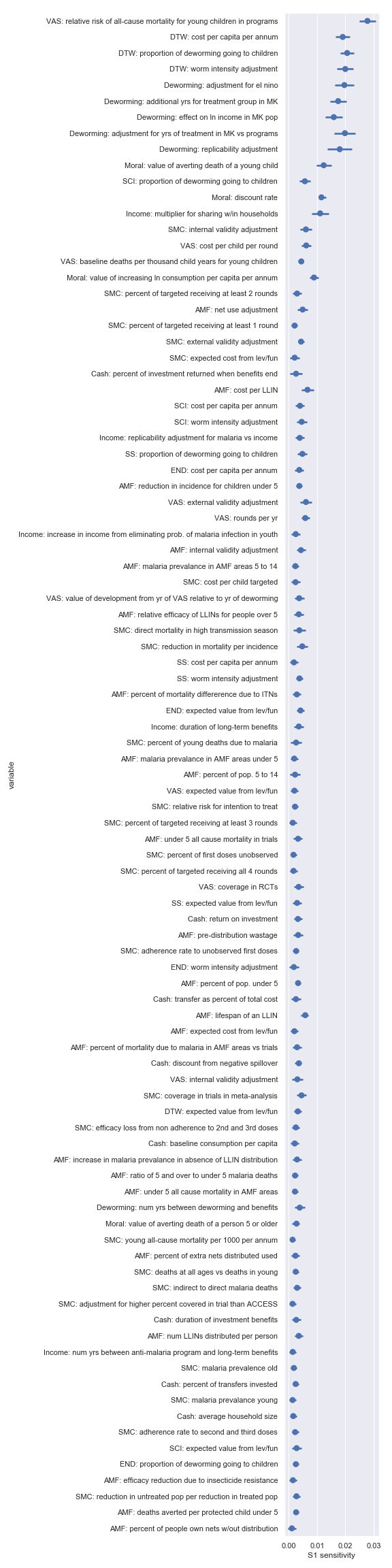

Delta moment-independent sensitivity analysis

Again, we’ll have three big plots, one for each distance metric—footrule, tau and angle. In each plot, there’s an estimate of the delta moment-independent sensitivity for each input factor used anywhere in the GiveWell’s cost-effectiveness analysis (and an indication of how confident that sensitivity estimate is).

So these delta sensitivities corroborate the suspicion that arose during the visual sensitivity analysis—charity-specific input parameters have the highest sensitivity indicators.

The other noteworthy result is which charity-specific factors are the most influential depends somewhat on which distance metric we use. The two rank-based metrics—tau and footrule distance—both suggest that the final charity ranking (given these inputs) is most sensitive to the worm intensity adjustment and cost per capita per annum of Sightsavers and the END Fund. These input parameters are a bit further down (though still fairly high) in the list according to the angular distance metric.

Needs more meta

It would be nice to check that our distance metrics don’t produce totally contradictory results. How can we accomplish this? Well, the plots above already order the input factors according to their sensitivity indicators… That means we have rankings of the sensitivities of the input factors and we can compare the rankings using Kendall’s tau and Spearman’s footrule distance. If that sounds confusing hopefully the table clears things up:

| Delta sensitivity rankings compared | Tau distance | Footrule distance |

|---|---|---|

| Tau and footrule | 0.358 | 0.469 |

| Tau and angle | 0.365 | 0.516 |

| Angle and footrule | 0.430 | 0.596 |

So it looks like the three rankings have middling agreement. Sensitivities according to tau and footrule agree the most while sensitivities according to angle and footrule agree the least. The disagreement probably also reflects random noise since the confidence intervals for many of the variables’ sensitivity indicators overlap. We could presumably shrink these confidence intervals and reduce the noise by increasing the number of samples used during our analysis.

To the extent that the disagreement isn’t just noise, it’s not entirely surprising—part of the point of using different distance metrics is to capture different notions of distance, each of which might be more or less suitable for a given purpose. But the divergence does mean that we’ll need to carefully pick which metric to pay attention to depending on the precise questions we’re trying to answer. For example, if we just want to pick the single top charity and donate all our money to that, factors with high sensitivity indicators according to footrule distance might be the most important to pin down. On the other hand, if we want to distribute our money in proportion to each charity’s estimated cost-effectiveness, angular distance is perhaps a better metric to guide our investigations.

Conclusion

We started with a couple of problems with our previous analysis: we were taking cost-effectiveness estimates literally and looking at them independently instead of as parts of a cohesive analysis. We addressed these problems by redoing our analysis while looking at distance from the current best cost-effectiveness estimates. We found that our input uncertainty is consequential even when looking only at the relative cost-effectiveness of the charities. We also found that input parameters which are important but unique to a particular charity often affect the final relative cost-effectiveness substantially.

Finally, we have the same caveat as last time: these results still reflect my fairly arbitrary (but scrupulously neutral) decision to pretend that we equally uncertain about each input parameter. To remedy this flaw and get results which are actually meaningful, head over to the Jupyter notebook and tweak the input distributions.

Appendix

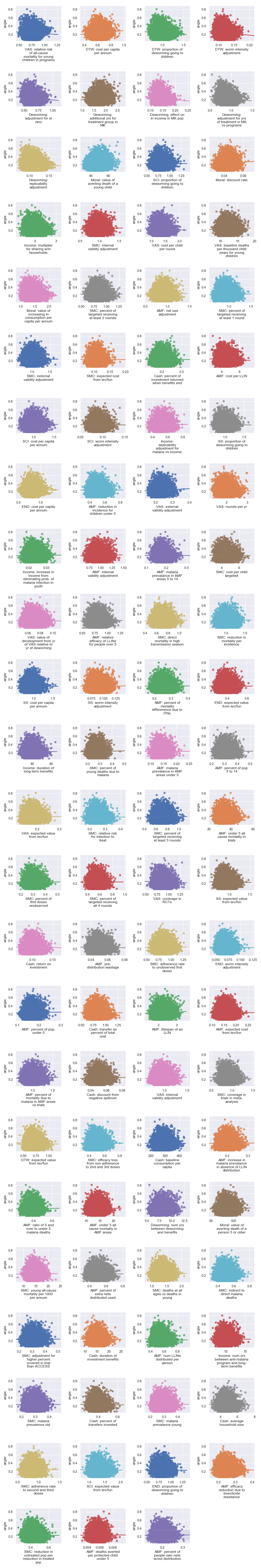

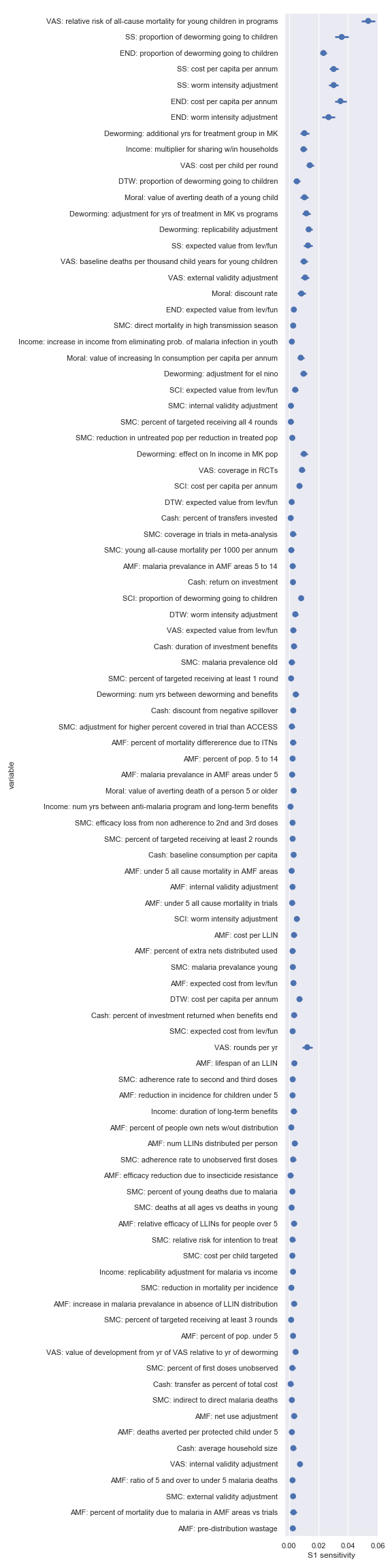

We can also look at the sensitivities based on the Sobol method again.

The variable order in each plot is from the input parameter with the highest \(\delta_i\) sensitivity to the input parameter with the lowest \(\delta_i\) sensitivity. That makes it straightforward to compare the ordering of sensitivities according to the delta moment-independent method and according to the Sobol method. We see that there is broad—but not perfect—agreement between the different methods.

If we just look at the probability for each possible ranking independently, we’ll be overwhelmed by the number of permutations and it will be hard to find any useful structure in our results.↩︎

The angle between the vectors is a better metric here than the distance between the vectors’ endpoints because we’re interested in the relative cost-effectiveness of the charities and how those change. If our results show that each charity is twice as effective as in the reference vector, our metric should return a distance of 0 because nothing has changed in the relative cost-effectiveness of each charity.↩︎