YAAS human cognitive architecture and learning

Yet Another Amateur Summary:

Sweller's Human cognitive architecture

Problem-solving relies on working memory. Working memory is very limited except when it comes to information that’s also in long-term memory. Long-term memory is thus central to expertise. Committing things to long-term memory (i.e. learning) is best accomplished by the careful management of cognitive load.

Contents

Preface

The following post is basically a straightforward regurgitation of (part of) (Sweller 2008). That paper is very readable so there’s really no reason to read the rest of this post. With that out of the way, I liked this paper for two main reasons:

- It fairly radically changed my opinion on the value of long-term memory in ways that are practically important

- It provides a coherent theory which unifies many phenomena. A coherent theory is easier to remember and easier to apply in novel situations than a disparate collection of facts.

Working memory

Essentially all human problem-solving is about the manipulation of items in working memory. Alas, our working memory is tragically limited—traditionally, research suggests the upper limit on the number of ‘chunks’ in working memory is the “magical number seven”. (Interestingly, there’s some evidence that chimpanzees have superior working memory to humans. Video and paper). Despite this grievous limitation, experience suggests that humans do actually carry out impressive feats of problem-solving. How?

Long-term memory

The key is exploiting a ‘loophole’—“huge amounts of organized information can be transferred from long-term memory to working memory without overloading working memory” (Sweller 2008). Thus, we arrive at the central importance of long-term memory to human cognition. Contra the denigration of rote memorization, “[task-relevant long-term memory] is the only reliable difference that has been obtained differentiating novices and experts in problem-solving skill and is the only difference required to fully explain why an individual is an expert in solving particular classes of problems” (Sweller 2008). In other words, long-term memory is necessary and sufficient to explain expertise.

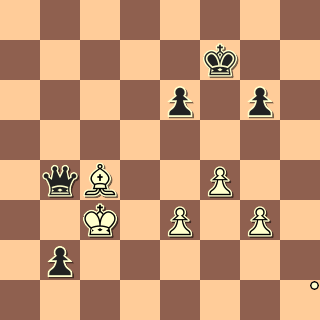

Chess board recall

We can make illustrate these claims with the results of a classic study (De Groot 2014). Look at the next image for a few seconds, close your eyes, and try to recall the positions of pieces.

If you’re a chess amateur, this should have been quite hard (i.e. you probably misremembered the pieces). On the other hand, if you’re a chess expert, this was probably fairly straightforward.

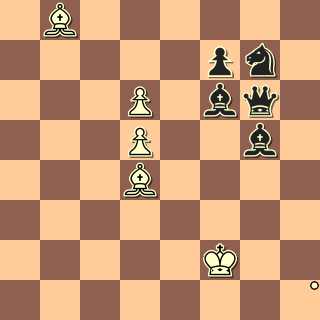

Now, look at the next image for a few seconds, close your eyes, and try to recall the positions of pieces.

Because this is a random configuration of chess pieces that would never arise in an ordinary game, experts and novices alike should find board recall difficult.

Researchers interpret this as strong evidence of the centrality of task-specific long-term memory in expert performance. Novices have no choice but to recall the type, position and color of 10 separate pieces. The demands of this task easily exceed the capabilities of working memory. Experts can encode the same information in larger chunks by referring to existing knowledge in their long-term memory. These results also count as evidence against some plausible alternative explanations of chess expertise. If there were some innate aptitude for chess, we would, contrary to the fact of the matter, expect to find some novices with accurate recall on realistic board configurations like the first image. If chess experts were just generally smarter or chess expertise had broad scope, we would, contrary to the fact of the matter, expect to find that chess experts had good recall for even the random board configuration.

Adding to long-term memory

If long-term memory is central to cognition, the question of how to add more information to our long-term memory naturally arises. (Sweller 2008) suggests that there are two possible modes of learning—deliberate transfer of deliberately constructed knowledge and random generation of propositions followed by tests for effectiveness—before concluding that “knowledge transfer is vastly more effective”. We won’t go into detail on random generation and testing here and instead skip straight to understanding how transfer works.

Cognitive load theory

The unifying framework here is ‘cognitive load theory’. Cognitive load refers to the demands placed on working memory and cognitive load theory says that there are three key kinds of cognitive load present in any knowledge transfer situation—intrinsic cognitive load, extraneous cognitive load, and germane cognitive load. Intrinsic cognitive load reflects the essential complexity of the material to be learned. Extraneous cognitive load reflects the incidental complexity arising from instructional design. Germane cognitive load reflects the effort required to transform and store the information to be learned. Because these three types of demand for working memory are additive, optimizing learning in the face of our supremely finite working memory amounts to minimizing extraneous cognitive load and maximizing germane cognitive load, especially in the face of subject matter with high intrinsic complexity.

Applications

We can briefly see the practical value of this theory by listing some of the instructional recommendations it generates:

- Worked example effect

“[N]ovice learners studying worked solutions to problems perform better on a problem-solving test than learners who have been given the equivalent problems to solve during training” (Sweller 2008). The attention devoted to the problem-solving procedure leaves less available for germane cognitive load and committing the correct procedures to memory.

- Split attention effect

If non-redundant instructional information is presented in two separate sources (e.g. in a diagram and in a textual description), learners must mentally integrate the information which imposes extraneous cognitive load. This impairs learning.

- Redundancy effect

If redundant instructional material is presented (e.g. a textual description of blood flow in the human circulatory system which repeats information available in a diagram of the body with arrows), it impairs learning. Examining unnecessary information and attempting to integrate it imposes extraneous cognitive load.

De Groot, Adriaan D. 2014. Thought and Choice in Chess. Vol. 4. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

Sweller, John. 2008. “Human Cognitive Architecture.” Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates New York, 369–81. http://www.csuchico.edu/~nschwartz/Sweller_2008.pdf.