YAAS Reading: Most of us read with our eyes and our brains

Yet Another Amateur Summary:

Rayner et al's So Much to Read, So Little Time: How Do We Read, and Can Speed Reading Help?

Contents

I spend a lot of time reading. But I’m not actually reading very quickly. The typical educated adult reads at about 200 to 400 wpm (for context, a speaking rate of 150 to 160 wpm is comfortable). Given that, it seems possible that a better understanding of reading could help me spend that time better. So I read (Rayner et al. 2016). Spoiler: It didn’t transform the way I read (and reaffirmed that speed reading is rather less than advocates claim), but it was definitely interesting. The regurgitation that follows focuses more on the article’s description of the ‘how’ of reading and less on the debunking of speed reading.

Speech > writing

Speech is prior to writing. Spoken language is thought to have originated around 100,000 years ago; written language 5,000 years ago. All human societies have spoken language; not so for writing. No natural language is purely written. Children learn to speak and interpret language without explicit instruction; not so for reading. Thus, we reach the claim that reading and writing is an “optional accessory that must be painstakingly bolted on” (McGuinness 1997).

After this bolting is complete, many of our reading processes are still mediated by our more fundamental spoken language processes—even during silent reading:

For example, when researches asked silent readers to rapidly decide whether words belonged to a category, homophones produced incorrect “yes”es 19% of the time (whether “meet” belongs in the category food) compared to the base rate for orthographically similar words of 3% (whether “melt” belongs in the category food1). The implication here is that we have difficulty translating directly from visual input to units of meaning and this visual-meaning connection is often mediated by the auditory representation.

In a different study, researchers asked readers to repeat an irrelevant word or phrase aloud while reading in an effort to impede any subvocalization. These readers performed worse on a subsequent test of comprehension than those asked to repeat a sequence of finger taps.

So our brains aren’t great at reading. But neither are our eyes.

Our eyes are terrible and wonderful

Acuity

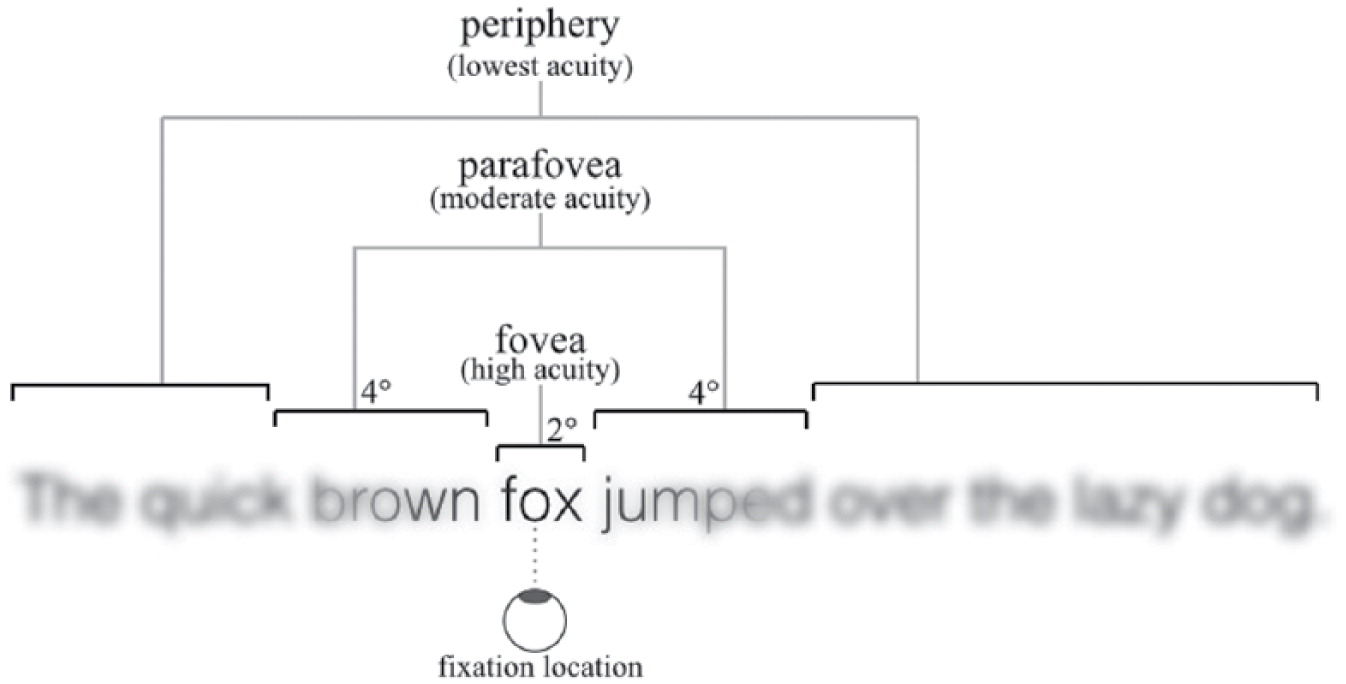

Our visual field is divided into three concentric circles. Most central is the fovea which extends from the absolute center to the circle 1° of visual angle away from it; this is about the size of your thumb held at arm’s length. The next circle is the parafovea which extends from 1° to 5° from the center of vision. The periphery encompasses anything beyond this.

When a word is presented so briefly that readers have no time to move their eyes, accuracy is high when the word is centered in the fovea. But accuracy drops off rapidly till it’s no better than chance at around 3° from the center of vision.

Part of the story here is that cones (the detail-oriented, bright light photoreceptors) are concentrated in the fovea while rods (sensitive primarily to brightness and motion in dim light) increase in concentration with distance from the fovea. Yet more interesting, inputs from rods are pooled before being relayed to the brain. That is, if half the rods in a group are fully lit and half are in total darkness, the brain will receive a signal indicating middling illumination. Cones, in contrast, would signal a light/dark boundary here because each has an unmediated connection to the brain.

Movement

Because our region of focus is so limited, readers must necessarily move the focus of their eyes along text via saccades (short, ballistic movements of both eyes)

Each saccade lasts roughly 20 to 35 ms and spans (in English) about 7 letters.

“Return sweeps” (long saccades moving your eye to the beginning of the next line) are often imperfect but are quickly corrected with a follow-up saccade.

Fixation

Between saccades, the eyes are fairly stable. These stable periods are called fixations and last about 250 ms. However, studies have found that reading behavior and comprehension is unaffected when each word disappears 60ms after the beginning of fixation (that is, our eyes continue to stare at now blank space). The remaining portion of the 250ms appears to be devoted to some essential higher-level processing which most occur before we can proceed to the next word.

For many words, adult readers recognize all the letters simultaneously2. This is limited by visual acuity as we discussed above—the word identification span is only about 7 characters to the right of the fixation point. Thus, long words require at least a saccade and multiple fixations.

From squiggles to meaning

Words are the basic unit of meaning in language3. So they are the first step in building from raw visual input to real communication. In fact, studies indicate that word-identification ability is the best determinant of reading speed (though skilled readers also have shorter fixations, longer saccades and fewer regressions4)

In turn, the best determinant of word-identification ability is the frequency with which the reader has seen the word5. Common words like ‘house’ are more quickly recognized than uncommon words like ‘abode’. This word-frequency effect has been measured in lexical decision tasks (Is the string of characters a word or not?), naming tasks (Read a word aloud as quickly as possible), and categorization tasks (Does the given word belong in a semantic category?).

Some words (homographs) can’t possibly be assigned a unique meaning without context. Sentence context helps disambiguate these words.6 Interestingly, contexts that make the next word very predictable often lead to the word being skipped entirely (i.e. the saccade moves over the word entirely and it receives no fixation). This happens about 30% of the time.

(This all begins to sound very Bayesian.)

Readers slow down a bit at the end of sentences and phrases. So there is some yet higher-level processing that occurs even after words have been been translated into units of meaning.

Speed reading

Much of the technology (e.g. Spritz) and teaching around speed reading supposes that the problem is just about getting your eyes through the words as fast as possible. This isn’t accurate. The limiting factors for reading speed seem to be primarily cognitive.

Rapid serial visual presentation (RSVP) precludes regressing to previous words, but this is a normal and healthy part of reading. Preventing it impairs comprehension. Additionally, having a preview of words to come (impossible in the RSVP setup) in the parafovea somewhat increases reading speed. All you get in exchange for these losses is the omission of saccades. But saccades aren’t wasted time, relevant cognition can continue while the eyes are in transit.

Speed reading advocates often suggest eliminating subvocalization. As discussed earlier, this is extremely difficult given the primacy of spoken language and impairs comprehension.

They also often advocate for “taking in” larger chunks of text—whole lines, paragraphs or even pages of text at once. As the discussion of the visual acuity highlights this is impossible.

Reading better

As mentioned earlier, more exposure to a word makes its subsequent recognition faster. Thus more reading will improve the all-important speed of word identification. More reading will also improve your predictions of upcoming words and improve your ability to synthesize and extrapolate from missing information (The authors suggest that this is part of what’s happening in speed readers. Intelligent people that spend a lot of time reading are good at filling in the gaps to compensate for their low comprehension at the purely linguistic level.)

The authors also highlight that skimming is sometimes appropriate and merited. When this is the case, skimmers should pay special attention to headings, paragraph structure and key words. Paying equal attention to all content is a poor use of limited time.

If you find the modesty of these suggestions discouraging, I quite understand. But, the authors conclude that, as in so many things, there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch. There’s a fairly inescapable trade-off between speed and accuracy in reading.

Summary

Speech is more fundamental than writing. Reading is mediated by spoken language in surprising ways.

Our eyes have very limited acuity. As such, we must saccade from one word to the next. In between saccades, we fixate. In each fixation, a word is most often recognized as a gestalt unit. Our ability to recognize words depends on both local context (other words in the sentence) and a larger context (our history of reading and our knowledge of the world).

Speed reading doesn’t work.

The only credible suggestion for becoming a faster reader is: Read more.

McGuinness, Diane. 1997. Why Our Children Can’t Read, and What We Can Do About It: A Scientific Revolution in Reading. Simon; Schuster.

Rayner, Keith, Elizabeth R Schotter, Michael EJ Masson, Mary C Potter, and Rebecca Treiman. 2016. “So Much to Read, so Little Time: How Do We Read, and Can Speed Reading Help?” Psychological Science in the Public Interest 17 (1). SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA: 4–34. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1529100615623267.

Though I’d argue that a homograph (“melt” as verb vs melt sandwhich) is a confusing choice of example.↩︎

The Stroop effect is an easy example of the automaticity of this process in practiced readers.↩︎

A regression is a backwards move in the text to a previous word. Skilled readers do this 10-15% of the time.↩︎

It’s unclear to me at the moment whether they mean absolute or relative frequency. If I look exclusively at unusual words, does that only improve my ability to recognize them rapidly? Or does it also degrade my ability to rapidly recognize common words? By distorting my prior?↩︎